large-scale murals

I was a maid at the Old Faithful Lodge in Yellowstone Park in the summer of 1978, between my freshman and sophomore undergrad years. I was cleaning the bathroom mirror in one of the cabins, when I saw myself in the mirror and the realization hit me: I am not a princess. I don’t know how that idea got into me, that I was a princess. I don’t really recall my dad calling me “princess”. I must have picked it up from the society at large, fairytales or Disney films.

In the most positive light, we wish for our daughters to be princesses in the sense that we wish for them to be safe and well-cared-for, to be “taken care of”. Of course, though, the life of a princess is a trap. It is a gilded bird cage in which a female endlessly primps an embodiment of beauty. A princess has no real power. Focusing on external beauty as a full-time, life-long project is a disempowering waste of time and energy.

My goal in the piece is to raise questions about whether it is helpful to call a female child “princess”, and whether it is wise for the society to nurture the fantasy in little girls’ imaginations that they are princesses.

The piece imagines my father’s heaven. He is teaching a saint how to golf. My dad loved to golf. It was his true happiness. I have included several of my other relatives who have passed on, as well as my best friend Lynnie who died from alcoholism during the pandemic. I have depicted her happy in heaven curled up next to her boyfriend-musician saint. My relatives are keeping Dad company as he is playing golf. They sit on the sidelines enjoying the day with a picnic.

The experience of creating this painting has healed my upsets about their passing. I see how happy they are. They are doing what they like to do, and I feel acceptance and resolution.

This piece is a large-scale acrylic painting on unstretched canvas. I use self-portraiture in all of my work. I shoot digital images of my face, hands, feet and clothing shapes and print them out for my source images, cobbling the composition together with additional google images (of pool table, rack, pool cues and balls). For this piece I was interested in using a similar expression on my face for both sides of an “emotional coin” (a hopeful-for-acceptance side and an obdurate-refusal side). The piece was created during my “pins and needles” period of waiting between being granted a tenure-track position and actually securing tenure. In a broader context, the piece is about societal hierarchical power dynamics; with the hopeful worker aspiring for respect and inclusion in contrast to the harsh authoritarian’s tendency toward withholding acceptance. The fact that the piece is created through self-portraiture highlights the point that we can choose to play either role and invites empathetic understanding. Exaggerated liberties with scale and shifting points of view place the viewer low in the picture space, below the power broker. The belt buckle is a symbolic reference to the patriarchy’s relentless insistence on dominance.

The piece harkens to the Armand Hammer Collection’s John Singer Sargent “Dr Pozzi at Home” 1881. That painting has lodged in my psyche due to the prominence with which the Hammer used to present it as the first work one viewed upon entering their space. For years it reigned supreme.

That piece depicts a male, highly-situated in the social structure, with somewhat feminine characteristics of posture, hand shapes and disposition. “Beggar Prince” depicts a female with somewhat masculine aspects. My work tends toward androgyny and is derived from self- portraiture.

Psychological issues of power, control, anger, repression, oppression and determination are at play. The title suggests a restricted level of societal power, as the female is not permitted the level of king, achieved through extensive effort and humility.

I am interested in the notion of accessing essence through the pathetic. As I see it, this strategy is evident in the late works of Guston and in the late self-portraits of DeChirico.

This piece is based on my family dynamic comprised of intelligent people who love one another but don’t seem to enjoy being together at the dinner table. The faces are all my own, derived from digital self-portraits. I am trying to express the various emotions I feel in this dynamic: wanting to escape, complaining about why things are the way they are, and feeling compassion.

The light fixtures, functioning or not, don’t really shed light on the situation. The studio lamps also seem to suggest to me, in conjunction with the empty supper bowls, a theatrical set. It is said that we are all actors on a stage in this life. That it is all an illusion playing out to support our growth.

Loosely referencing the bus stop in my neighborhood, this piece is my nod to “Waiting for Godot”.

How do we live our lives? Waiting with dread and projected worries born of past disappointments, or in an agitated state of dissatisfaction rooted in impatient desire for what is out of reach, or in fearful anticipation focused solely on the future or breathing in the moment’s bliss.

The little girl on the trike represents the powerful, joyful future. She will lead with humble honesty and sincerity. She is our hope.

I’d been feeling like a tired cheerleader, tired of encouraging myself as an artist and adjunct art professor. I thought it might be interesting to contrast that emotional fatigue with another character which embodies the commercial representation of a successful person enjoying the “good life” with a hyper-happy, superficial veneer of enjoyment.

“Fountain” was inspired by a little girl I saw enjoying the fountain while I was seated at an outdoor café near Los Angeles County Museum of Art. I was struck by the recollection of how thoroughly we enjoy being alive, being in the moment, when we are very new to the experience of life. The figure with the briefcase represents adulthood, when we are striving to “make it”, to maneuver successfully through the society. I am trying to suggest the extreme level of “high-alert” (fear, adrenaline) state of mind during this phase of life, which is so stressful and draining to our life force. The older, seated figure indicates that society makes beggars out of the majority of the population. Tired and exhausted from years of stress and often the resultant stress disorder, trying to make it all work out and add up, worrying all the time that despite the axiom of hard-work and trying one’s best as being a formula for success, that one will fall short nonetheless.

“Kiddie Pool” is comprised of two pieces of 72 x 54 unstretched canvas resulting in an overall dimension of 73” x 106” (approximately 6 feet x 9 feet). The faces are self-portraits. As always, I play all the characters’roles in my work.

This piece was inspired by a scene I saw while walking through my neighborhood of El Sereno on the eastside of Los Angeles. Some children were playing and laughing in a kiddie pool that was situated almost right on the sidewalk, as their front yard was very small. They seemed oblivious to their situation of poverty, as they fully enjoyed themselves, unselfconscious despite their lack of privacy or space. Either they were not yet cognizant of their rung in the social hierarchy or they were able to not let that lack infiltrate their being in the moment.

The woman with one shoe is older and still in the situation of poverty. But now the poverty has stuck on her, and this lack dominates her life. The blanket she clutches is included to suggest the security blanket we associate with childhood. I am proposing that she too is still a child, as we all are, but that the years of poverty have clung to her and have taken their toll.

Basically, the piece is about old poverty and new poverty and the erosive effect that poverty has on the human consciousness.

“Laundromat” is comprised of two pieces of 72 x 54 unstretched canvas resulting in an overall dimension of 73” x 108” (approximately 6 feet x 9 feet). The faces are self-portraits.

The setting is based on images shot in a local Laundromat in El Sereno. I have tipped the shapes and emphasized the peeling linoleum to heighten the decrepitude and neglect, hearkening to the sad state of the current economic/social structure.

The ordered, routine circuit of the carousel has been disrupted. Chaotic, violent upheaval serves as a metaphor for the current national and global economic/political foment.

The horses are in varied states of metamorphosis, inanimate mannequins becoming alive, veering into abstraction. The subject matter, as well as the emotive and subjective use of color dialog most closely with historical Fauvist Franz Marc of Der Blaue Reiter (the Blue Rider) Group.

I was leaving my mechanic’s shop in North Hollywood when I saw a woman on a moped- like vehicle paying a man (mechanic? worker?) from an impossibly small purse that was perched on her sternum. It struck me as a comical.

This acrylic painting on unstretched canvas is comprised of two pieces of 54 x 72 canvas abutted in an overall dimension of approximately 6’x9’.

This whimsical, flight of the imagination offers a fantastical underwater scene at an ocean bed psychic reader’s shop and tea room. Visible through the beaded curtain is the adjoining living quarters. The psychic has a “live one” in the gullible customer who is taking the bait of the conjured tale she dangles before his gaping eyes. Evident in the crystal ball is the psychic’s real perception of her client as a clownish fool.

Some of the creatures depicted are composite part human/part animal beings further bending the logic of this incredible world. The open book alludes to the narrative structure, the beginning of the tale (i.e. “boar walks into an underwater psychic’s shop…”). The narrator’s wife incessantly yammers on, spinning the never-ending storyline, “Anyhoo….”

I felt compelled to address the oil disaster in the Gulf of Mexico. The large figure was originally intended to represent my feelings of anger, frustration and revulsion with the incessant pollutants bleeding into the ocean ecosystem. Paradoxically, I found he also suggests man’s befoulment of the seas. The gourmand who is slurpily savoring bonbons was originally intended to represent an oblivious, society-as-usual response in the face of the crisis. She exercises discriminating taste in her indulgence while disregarding the catastrophe around her. Funnily, I felt she came to be a loving grandmotherly character dropping bits of hope and safe harbor.

The exultant dancer embodies the notion that all is perfect in the universe at all times even if we cannot understand how everything fits into a great cosmic plan. The lone fox is deeply saddened by Little Brother’s gargantuan foolishness.

I included the little jerboa simply because I couldn’t resist him (after Jacopo Ligozzi, late 16th century). Who will survive? The rower, fashioned with an organ-grinder monkey in mind, is frantically over-whelmed with the task of trying to steer the gravy-boat-like vessel. Panicked, he asks help to solve the tragedy. How?

It was my intention to create a piece that reflected on the various stages of life. I envisioned a tree, akin to the Bodhi tree, whose roots reached all corners of the earth and from which sprung all manifestations of life and the concomitant psychological postures that typify those periods.

The cactus that busts the crib suggests a traumatic rupture in the early years and alludes to a broken home. The child holding ice skates finds herself in an austere and chilly landscape, cognizant of the situation and worried by the projected ramifications. (I am reminded of Charlie Brown’s Halloween treat of a rock, saying “I got a rock”, in her case, a moon rock!) Conversely, the cat basks in the glow of bountiful affection with the chocolate cake suggesting a maternal demonstration of love. The polarized psychology of the cat and the child humorously captures the contrapuntal condition of the haves/have-nots mental framework.

The braying, angry sheep represents the barking noise of society as a gaping maw of unmet craving. Meanwhile, the yogi balances nimbly on the tree of life with clear focus, an open heart, and an awareness of the tragi-comedy that is life’s journey. The crutches and wheel chair represent the failing physicality of the older years. Weaknesses now appear on the horizon.

The little bull dog was intended to suggest old age’s fond farewell to life with a sentiment of gratitude and appreciation for the experience of life amidst the condition of still not understanding its mysteries.

“Rush” is comprised of two pieces of 72 x 54 unstretched canvas resulting in an overall dimension of 72 x 106 (approximately 6 feet x 9 feet). The left side of the piece conveys the rush of life crowded with people, the pushing, the forward-driving impulse of living.

This striving is suggested in the faces. Some reflect the anger and frustration in the face of the daunting struggle to attain status/meaning/a place in the world. Some, with eye-on-the-prize, pin-pointed focus get nearer it seems, and yet we see faces revealing to various degrees a dawning realization that one will likely fall short of these aims. Faltering with waning strength, dreams slip through fingers, just out of reach.

The rush of water signals a profound break in the noisy clamoring of life. The right section of the piece indicates a quiet, immense space. The upside-down tree’s roots grow into the nighttime cosmos, its leafed branches underground. Is this the space after life, the underworld, the “then”? The bared figure in the placid bath/casket/cocoon, is she asleep, meditating or dead? The white foal looks back at her before moving toward the mysterious headlights in the sky. Is he her animal spirit or does it represent an elegy to youth? Undeterred, the rush goes on.

It was my intention to create a piece that expresses the exhaustion I feel of late. In articulating the faces, I became aware of underlying emotional subtexts of whining dissatisfaction, complaints, reluctance, despair, hopelessness, self-pity and anger. I was reminded how often when asked if I am angry, I commonly reply, “I’m just tired”.

As the painting progressed, I noticed that the hands of the figures were very powerful, like laborer’s hands. These people are workers. But they are not in action. They are idle, in limbo, or perhaps “out to pasture” in the ranks of the unemployed.

The bunnies represent the generally benign, pacifist nature of the typical American citizen. They also symbolize proliferation, the endless production of more and more humans “coming down the pike”. Having recently read Richard Adams’ “Watership Down”, I found his examination of the varied societal structures that the band of journeying rabbits encounters to offer a pertinent inquiry into the ideal social pattern for optimal liberty and happiness. In the meantime, so many people, so tired.

A mural-scale acrylic painting composed of three pieces of approximately 8’ x 11’ unstretched canvas, “Party Life” is a psychological story that parallels America’s ascendancy and state of decline in an allegorical microcosm that follows the life of a party as an emotional mirror. (Part 1: Pre-Party, Part 2: The Party, Part 3: The Aftermath).

Amidst the journey are issues of aging, death, and loneliness. The most significant parallel storyline follows a girl’s hopes for the party, her meticulous preparation for the party, her falling head over heels in love, and her crushing self-effacing realization that she functioned only as an object of sexual exploit. The bare ass references the target of her, that is to say, the seemingly sole zone of import. In the final panel, she wails at the negation of her personage, the empty nullification of her worth as a unique being. The scenario matches the military/industrial complex’s dismissal of America as an object of financial exploit, obdurately disavowing its value as a unique harbor of dreams made real.

This work is comprised of seven pieces of 72”x 54” unstretched canvas abutted next to each other in an approximate quarter-drop grid fashion. Basically, each piece delineates one of the character’s point of view. The scenario is the classic “girl walks into a bar…”. As the various characters pass through each other’s domain, we see their beings reconfigured to evince that individual’s “take” on them.

For example, as the man sits and sips his beer in the Tiki Lounge, we see him as a blue-collar worker with a world of responsibilities on his mind. As he passes into the woman’s realm to order another beer from the bartender, he is now perceived as a toxic, smarmy source of trouble.

In the bartender’s world, we see the bartender’s earlier persona in the award plaque photo on the counter as the face of optimism, eager toward the future. Now, as he addresses the woman’s request to use the restroom, we see his burnt out expression suggesting his loss of future’s horizon, succumbing to an existence of endless monotony. We see in the mirror reflection behind the bar, (loosely referencing Manet’s bar scene), his impression of the woman as a finicky female. As the woman walks toward the restroom, she pauses to pet the dog. Having entered the man’s territory, she is now perceived as “do-able”.

In the sleeping dog’s world, it’s all about shoes freighted with news of the outside world, while across the bar in the parrot’s arena we see the bird’s time-lapse antics and his perception of the girl as a brightly-colored, abstract shape. Below, the old woman chomping on pretzels perceives the girl to be a tramp. We see the old woman’s self-perception as an over-sized clown. As the dog and parrot enter her realm, she sees the evidence of the world’s toll on them. The dog is missing a hind leg (though as he dreams in his own zone he is whole) and the parrot is blind in one eye. Reflected in the cash register, we see the parrot’s read on the old woman, suggesting a frightened human daunted by dwindling health and resources in the face of aging. This brings us back full circle to the girl as she enters the bar. We see her reflection in the glass of the door and recognize that she perceives herself (probably a bit on the younger side) as a nice person, a little nervous and unsure of herself.

The aspiration of the piece is to further the notion of cubism by pushing the idea of multiple perspectives into the realm of psychological perceptions. Of course, underlying it all is the idea that we are all one (hence the use of Polaroid self-portraits to articulate all the various emotions). Also, the notion that in furthering the idea of time lapse, that the girl will eventually be/is in fact the old woman years later/now. Fundamentally, all the characters are the same at the core, wistfully vulnerable in the face of life.

Pulling imagery from my own life as well as invented characters predominantly drawn from cultural clichés, this thirty-four-foot-long acrylic painting follows the myth formula outlined in Joseph Cambell’s “Hero of a Thousand Faces”. Starting in the upper left corner, the hero awakens and is lead to the threshold of adventure where she tumbles into the sea. The gravestones evince her descent into death where she must contend with the unsavory guard to gain entrance into the next world which I have cast as a teetering circus of societal pitfalls. Throughout her journey she encounters adversaries as well as helpers who assist and guide her through the various realms until she returns full circle with the boon to the world.

The piece visits life experience from the female perspective, with the obligatory gestures and various roles she adopts as she maneuvers through the social structure. She reemerges a restored, illuminated female celebrating the contribution that is the female perspective.

exhibition installations

Public Art Outdoor Mural in North Hollywood, CA. 18 feet by 44 feet. On Chandler Blvd. between Vineland and Cahuenga.

small works

Cherie Benner Davis posted a photo of a flower arrangement on Facebook. I saw the image and assumed it was a painting because the composition was so terrific. She said, no it was just a photo of some flowers. I asked her permission to use the image to create a painting because I loved the composition so much. She said yes.

The composition struck me as embodying a very Cezanne-like strategy because it simultaneously celebrated symmetry and asymmetry. For example, in “Still Life with Plaster Cupid” and “Still Life with Vase of Tulips” the focal point is placed in the center of the pictorial space suggesting approximate symmetry. However, the viewer’s eye is quickly drawn to the visual weight and highly saturated colors of support elements in the mid to lower left side of the composition creating insistent asymmetry in a “shoe in the dryer” eye path, where the eye cycles throughout the composition and continually returns to the emphatic visual weight/color saturation in the mid to lower left.

I lost my best friend in the year of the pandemic. In this self-portrait, I am wearing the t-shirt she gave me when we went to a LACMA event years ago. I used four pieces of watercolor paper skewed at angles to suggest being in pieces and out-of-kilter from being hit with an unexpected tragedy. She died from alcoholism at age 58. She drank a lot more in her last year, the COVID year. She died on Feb 16, 2021. It was the first day of spring semester.

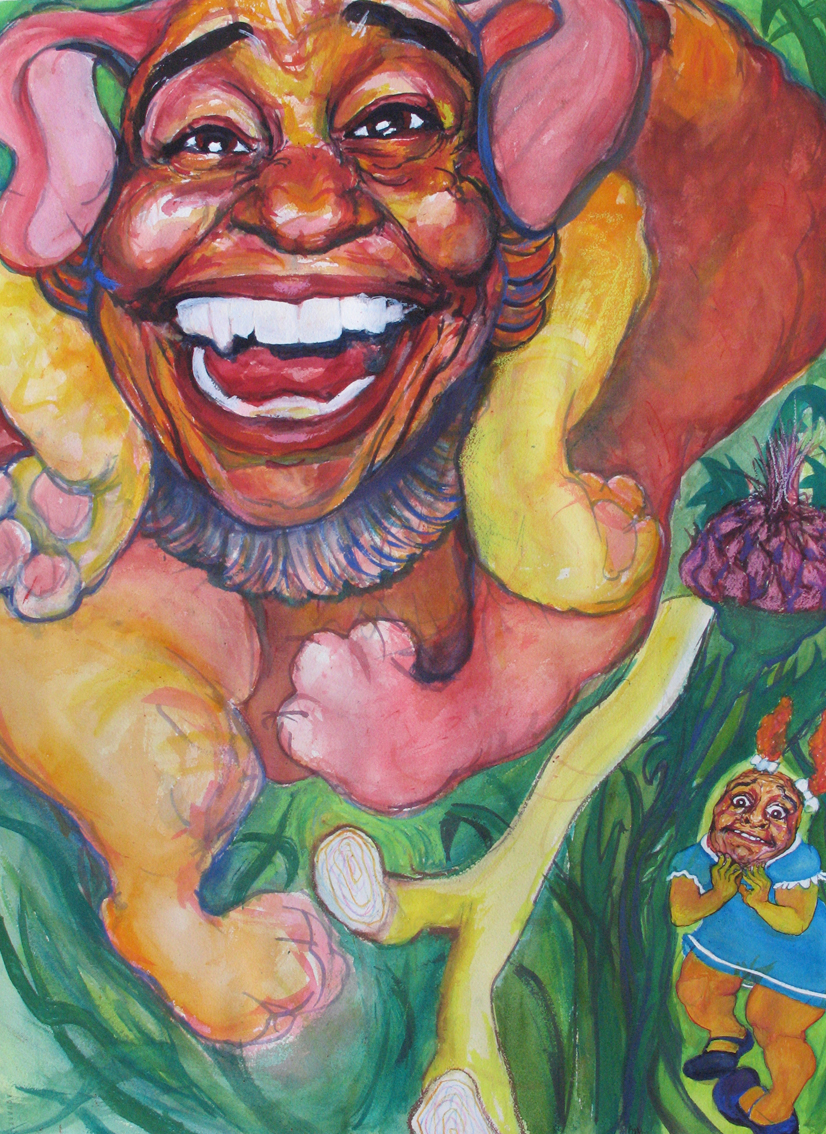

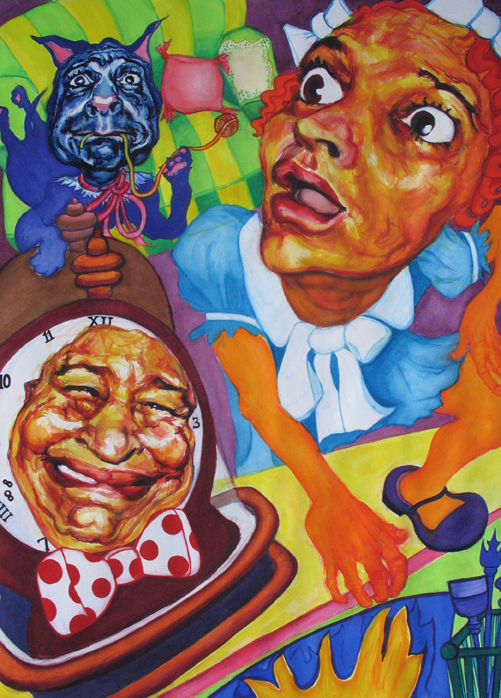

Alice series

“The Queen was in the parlor eating bread and honey”

Historically, in “children’s” stories, queens are involved in matters of food. Why food? Does it represent the only domain of authority for the matriarch? It would certainly seem so, as female power is traditionally asserted in our society in this one arena. Interestingly, the underlying psychology alluded to by Carroll’s characterization of the Queen, points to women’s “hysteria” not as an irrational outburst of exaggerated hormonally-driven insanity, but rather acknowledges the pent-up frustration of the female “leader” whose authority is relegated to the kitchen.

With savvy irony, Carroll articulates her rage in the words “Off with his head!”, when, in fact, as history has shown us, this will most likely be the outcome for her own head, as decapitation has been a common solution by the patriarchy to eliminate ‘the uncontrollable female’ (i.e. OJ Simpson). Parenthetically, please note that the Queen’s orders of execution are never carried out in the story. Ultimately, I assert that the Queen’s rage over seemingly minuscule tarts addresses the fact that, in truth, she is cognizant of her probable fate and that the fury we see is her aggravation at being powerless to change her destiny.

Other significant devices include:

1. Checkered table cloth references game board (i.e. Carroll’s chess game). Also, the four of clubs, plus the seven of clubs, plus the Jack of Hearts equals “21” in ‘Black Jack’.

2. A looking glass is a mirror: hence note mirroring in “Here ye, Hear ye” (letters reversed) which also serves as a play on words to reference Carroll’s frequent puns. Additionally, the pink and green figures on right mirror those on left.

3. Alice as innocent destroyer (her growth spurt creates ‘tsunami-like’ tidal wave of catastrophic proportions); hence her petticoat suggests waves.

4. Queen is angry over more than tarts (the “crystal ceiling” implied in cage-like ruby tiara droplets).

5. Soldier represents upholder of institution (issues of glory and duty manifest).

6. Jack of Hearts represents the comprehensible foibles of humanity under a relentlessly rigid system of “justice”.

7. Chaos within system of order moves from upper right to bottom left arriving ultimately to March Hare who receives bounty in split-emotion of fear and elation (the treasured tarts represent a fluke fortuity akin to the lottery) .

In reading the chapter “Advise from a Caterpillar”, I was struck by Carroll’s decision to make the caterpillar blue in color, never having seen a blue one myself. Given that the creature is smoking from a hookah pipe, speaking languidly, and is situated atop a mushroom, I deduced that it was the blue veins of the hallucinogenic mushroom’s stem that caused his coloration, and as such, the caterpillar therefore represents altered states of consciousness. I added updated ‘to-go” food remnants to suggest the “munchies” and I decorated the mushroom’s cap like a pepperoni pizza. I imagined the caterpillar to behave something like Brando in “Apocalypse Now” or like a Godfather mofia-boss with Caesar/guru-like trappings: hence, one of his feet is feeding him grapes, another is swabbing his forehead with a towel, and he has a couple of flunkies hanging around him soaking in the lifestyle.

Alice is depicted in wide-eyed wonderment at this fantastic spectacle. The view up her skirt references current day scrutiny and speculation on the nature of Carroll’s seeming fixation on six-year-old girls.

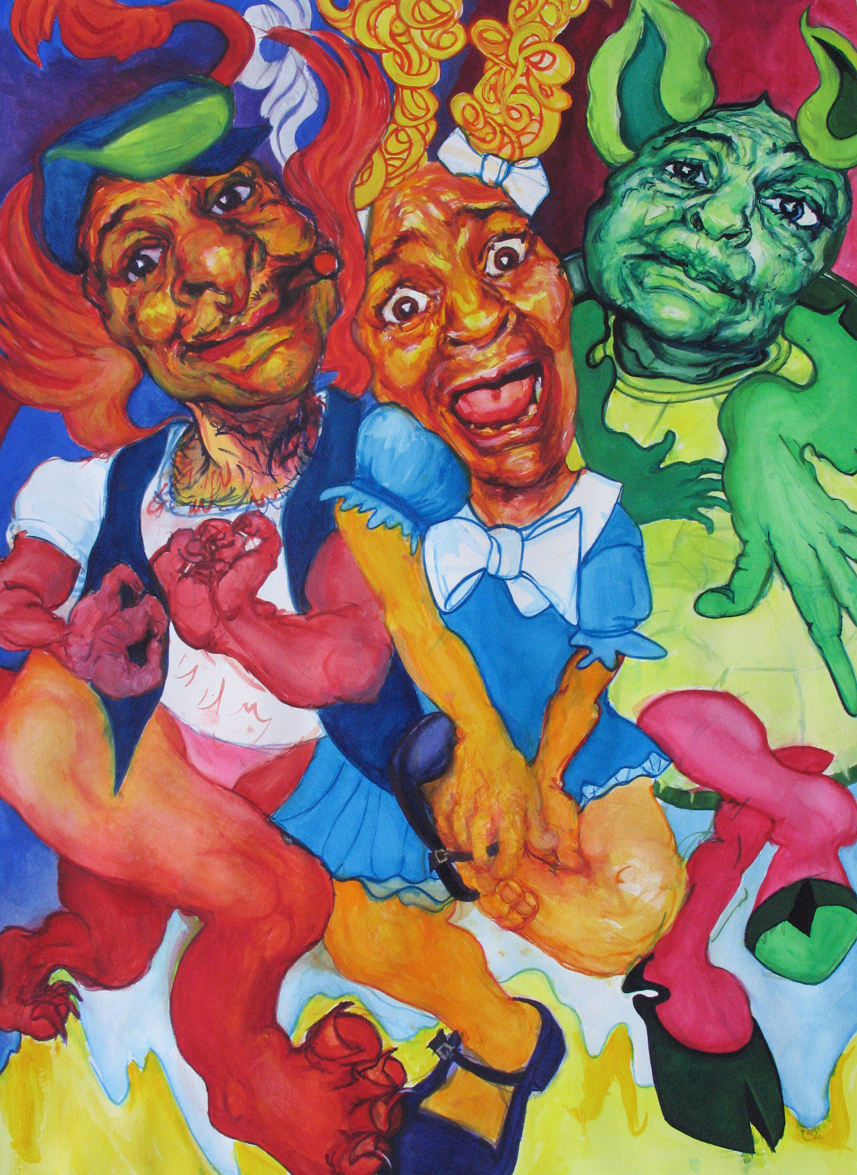

As the core of my artistic agenda is social critique in which I examine human emotional response to societal mores, I am using Lewis Carroll’s timeless classic “Alice in Wonderland” as a vehicle, drawing a parallel with Carroll’s astute analysis of social infrastructure. Through often misconstrued as a benign children’s story, (due to the assumed inference that Wonderland is a fantastically unreal place), one discovers very shortly that Carroll’s nightmarishly, grotesque world is not fanciful, but rather a brutally accurate mirror of real life. Notably, the work references the Freudian psychology of the “hysterical” woman who manifests in the Duchess’ House scene as 1) the overworked domestic (the cook), and 2) the overwhelmed mother (the Duchess). I assert that Carroll is sensitive to the rationality of the prospective outbursts and does not support the notion that their aggravated behavior signifies an inherent irrationality of hormonal insanity, but rather a comprehensible rage in response to unpermitted realization of potential (suppressed roles for female members of the society) and exaggerated responsibility (sole accountability in child rearing). Simultaneously, the oblivion of the patriarchy is articulated in the character of the fish livery man who is shocked and surprised by the display of violence, as well as the frog livery man who is privileged to indulge in philosophic meanderings despite his supporting role stature. (That is to say that though the Duchess’s title implies a claim to elevated hierarchical power within the society, in truth, she has less psychological freedom than her male servant).

Compositional devices include:

1. We enter the image behind Alice (the ingénue) who functions as our eyes, while multiple perspectives are employed throughout the piece in order to suggest the instability and chaos of the scene. Note: a) Checker board tile pattern references Carroll’s interest in chess, b), in seeing up her skirt I am alluding to the speculation around Carroll’s interest in six-year-old girls for his amateur photo shoots, but I am shifting Alice’s age up in hopes to make the audience more complicit in the sexualization of the young girl.

2. Traditionally friendly signage is inverted into antagonistic insult (the welcome mat says “Get Lost” and the familiar Irish saying is distorted “May the road rise up and swallow you whole” in support of Carroll’s position that adult society is not a cheery landscape. Also, the soup is updatedly acerbic in its level of toxicity (original version just suggests over-peppering, now a sickly-green concoction suggests radioactive proportions).

3. Cheshire Cat embodies a bretchian role, breaking the “fourth wall” as it intimates, in a gleeful aside to the audience, its amusement at the unfolding human drama.

4. Baby’s open eye evidences the child as witness, an innocent notary to the skewed goings-on. Additionally, the baby’s transformation into a pig infers its inevitability in repeating the abuse cycle.

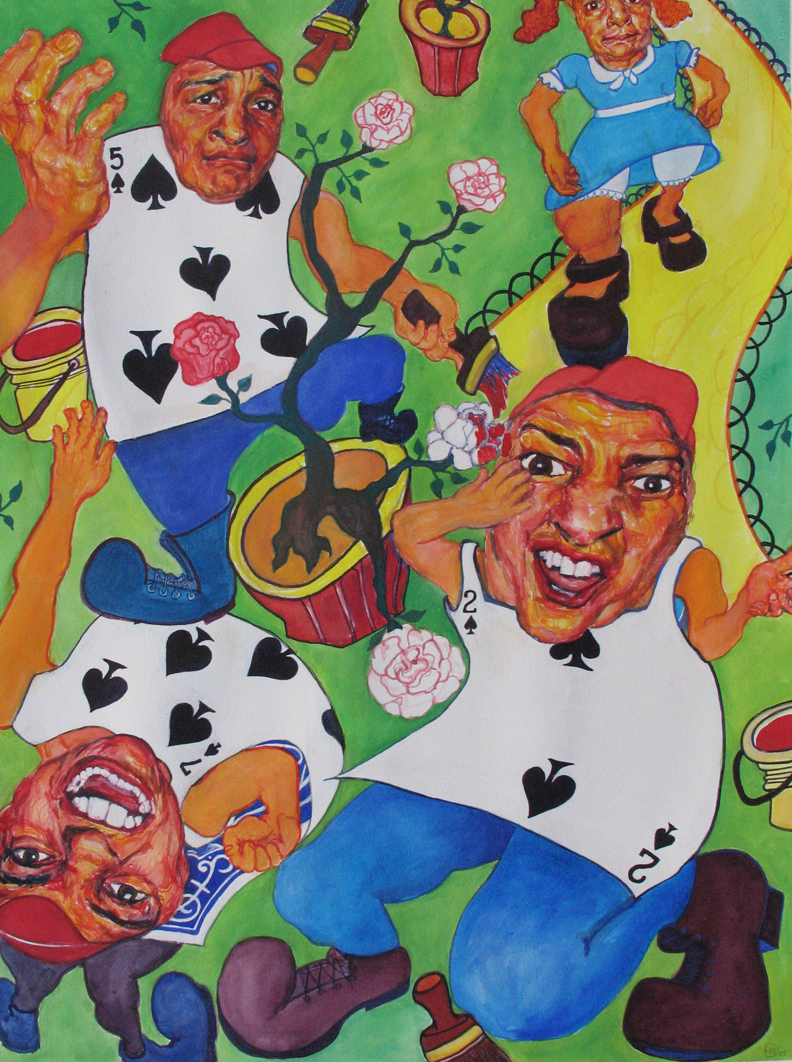

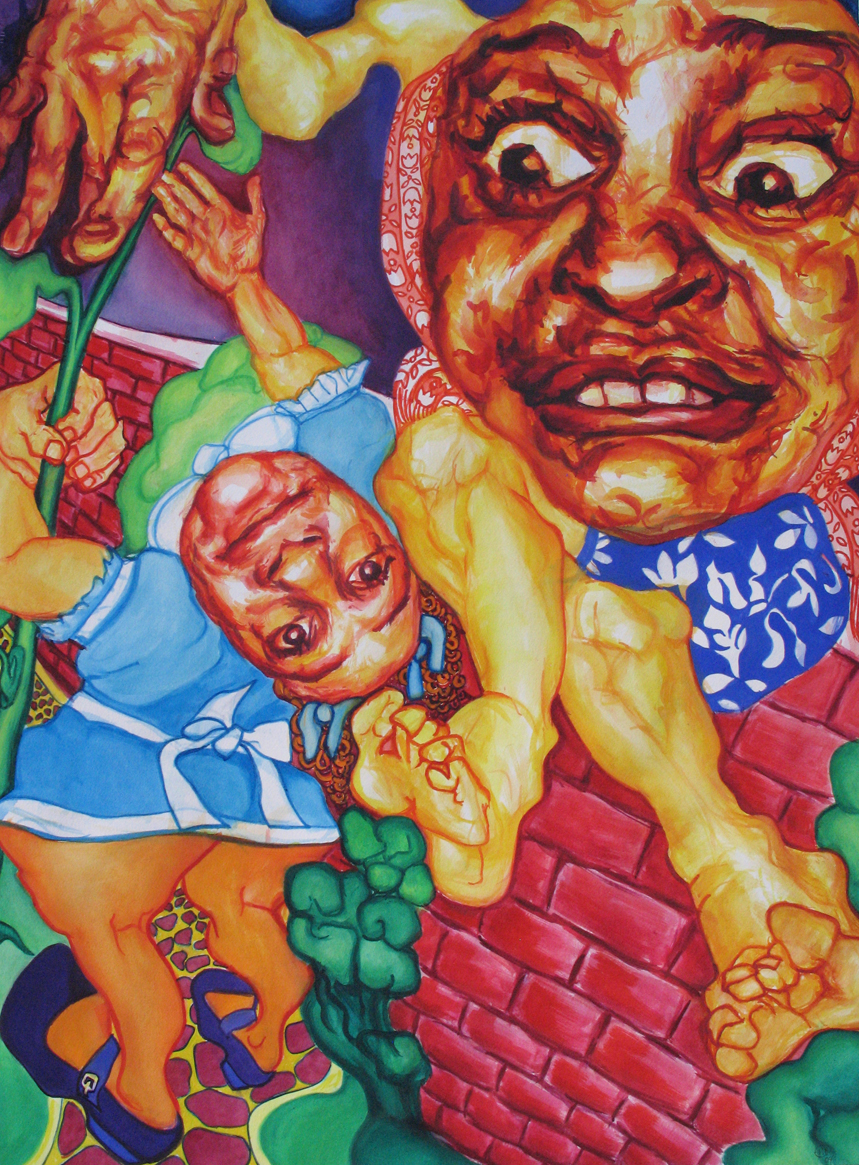

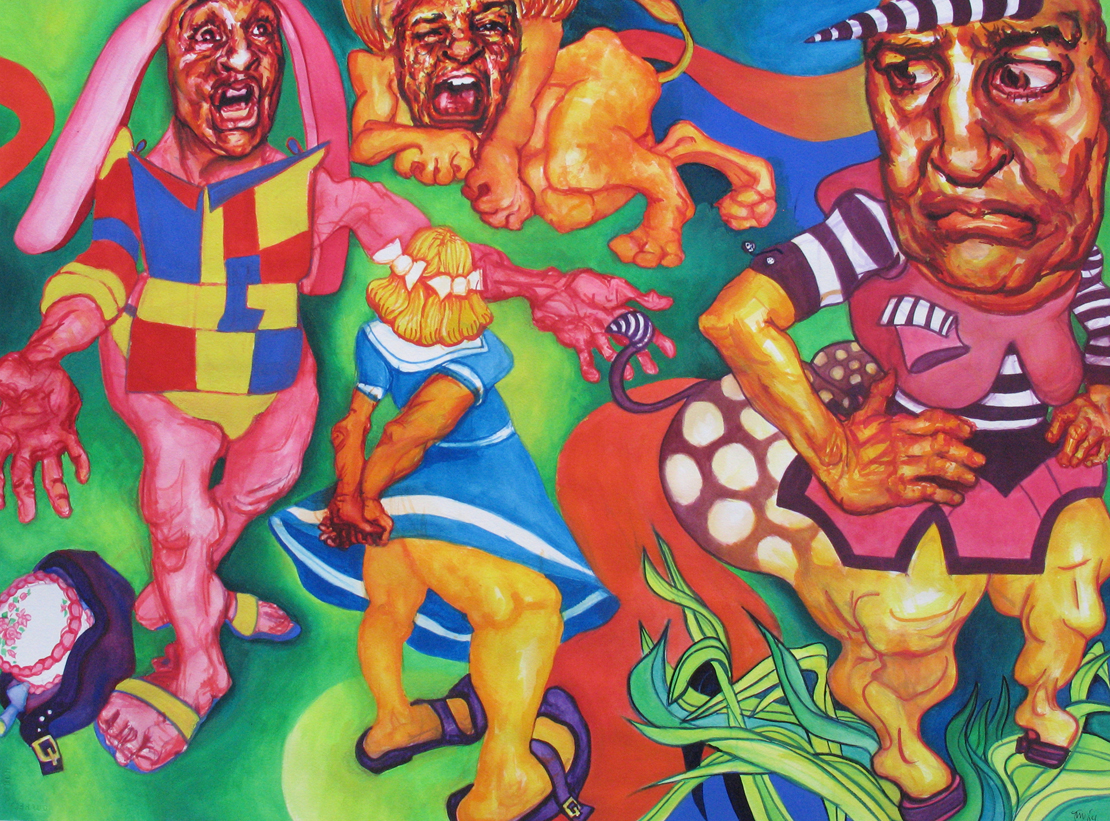

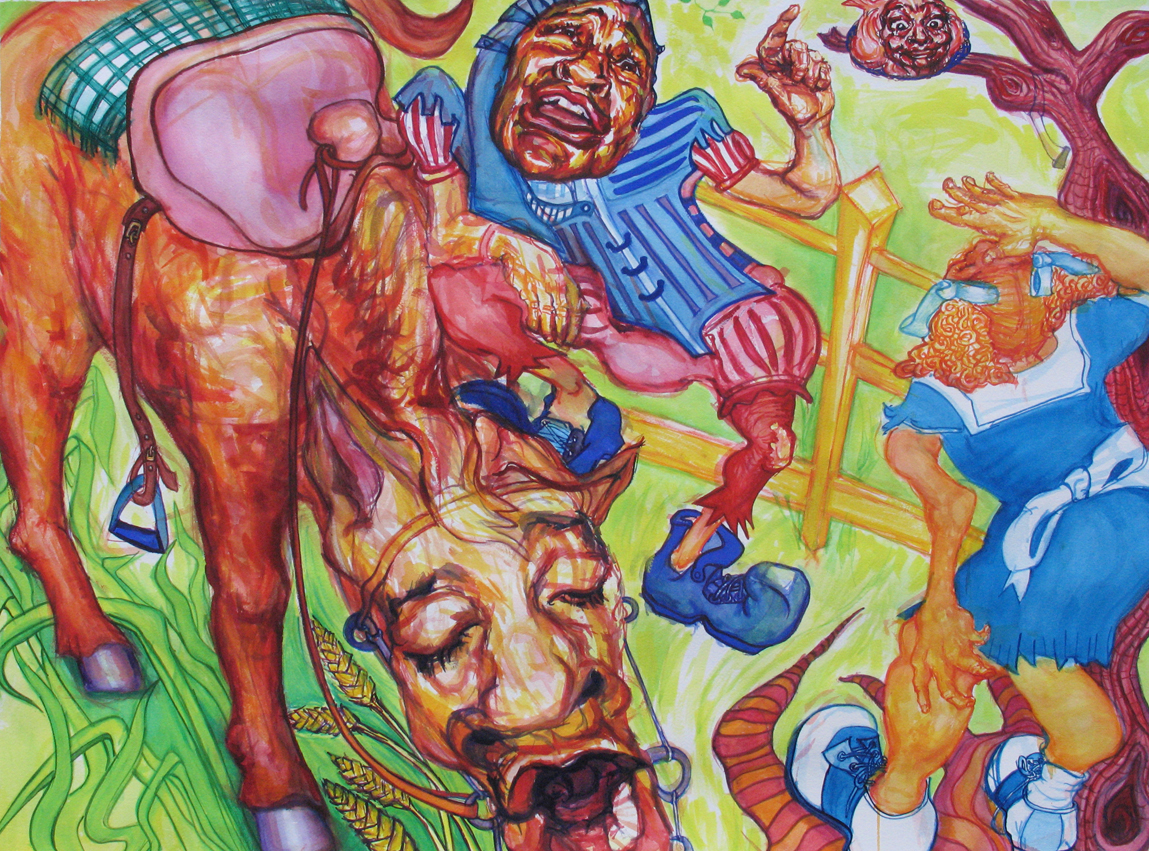

This piece depicts the culminating scene in the chapter entitled “The Queen’s Croquet Ground” from Lewis Carroll’s “Alice in Wonderland” in which the guests have broken into an all-out brawl as a result of the Queen’s incomprehensible dictates. According to her rule, the balls are hedge-hogs (which constantly unroll and attempt to slink away), the mallets are flamingos (which are impossible to control as they don’t want their head to be utilized as a device to whack at hedge-hogs), the arches are soldiers doing a back-bend (a position that is impossible to sustain for any length of time), and the playing field is riddled with ridges and furrows further rendering the game absolutely futile and aggravating to any individual attempting to succeed. I believe that Carroll offers this insanity as a metaphor for ineffectual governance, (not to mention government’s tendency to lack any empathetic sensibility for the affected members’ experience under its domain). He suggests that if you set up a system in which the individual cannot conceivably ascertain, with any modicum of rational thinking, a way to progress forward toward success within that system, chaos will inevitably ensue. In fact, he infers that it is a guaranteed recipe for anarchy.

Other significant devices include:

1. I have lifted some imagery from playing cards.

2. I used Polaroid self-portraits as the source material for all the facial expressions.

3. The composition is a radial plan with the action initiating from the center two fighting hedge-hogs. The extended arm shapes encourage the viewer’s eye to travel circularly outward, mimicking the dizzying effect of chaos.

4. The executioner (Ten of Clubs) is trying to explain to the King that it is impossible to behead a head if it is not attached to a body, as is the case with the Cheshire Cat in this scene.

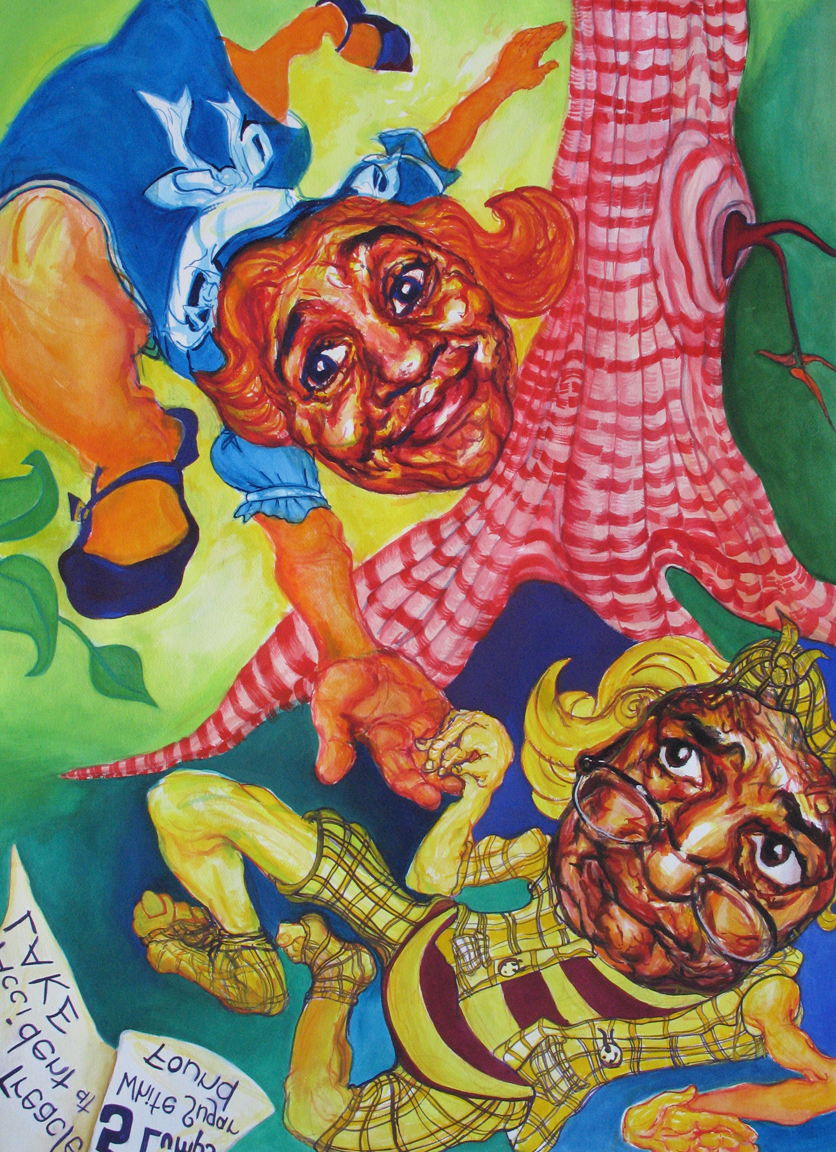

This image depicts the gryphon and the mock turtle inadvertently trampling Alice’s toes while showing her how to dance the lobster quadrille. The gryphon is described as being half-lion and half-eagle, arguably representing the king of the land and the king of the air. His eagle attributes of acute visual clarity suggest that he can see things as they really are, with great objectivity, which is why I assert that he functions as an exposer of self-delusion and self-perpetuated myths. For example, upon the Queen’s taking leave to see after the executions she’d ordered, he chuckles, “It’s all her fancy, that: they never executes nobody…” which is verified just a few paragraphs earlier when “…Alice heard the King say in a low voice… ‘You are all pardoned,’” (see the chapter entitled “the Mock Turtle’s story” in “Alice in Wonderland”). Further, though the mock turtle is relentlessly sobbing, the gryphon reveals that, in fact, the mock turtle has no real sorrow, saying “It’s all his fancy, that: he hasn’t got no sorrow”. Notice, too, that despite the gryphon’s presumably-elevated status within the animal kingdom, he speaks in the manner of a commoner, which then perhaps characterizes his astounding perceptivity as street-wise common sense. Coupling this with the “hjckrrrh” sounds he makes (which, for me, call to mind throat-clearing), I decided to cast him as a cigar-smoking cab driver, as he’s charged with escorting Alice around, saying “Come on!” all the time.

One definition of “mock” is “delude”. Hence, we have a deluded turtle, as indeed the gryphon has already informed us. Delusion is defined as a persistent false psychological belief, which is confirmed by the mock turtle’s tearful lamentation that he “once was a real turtle”, but apparently does not perceive himself to be real anymore. The recipe for mock turtle soup generally calls for veal. That is why I’ve designed the mock turtle with some turtle features and some bovine features (ears, hooves). Therefore, the mock turtle and the gryphon mirror each other not only in that they are both composite creatures, but because the good-natured, easy-going gryphon is happy with everything, whereas the mock turtle is melancholy and dejected over nothing. To visually allude to this psychological polarity, I’ve handled the gryphon predominantly in warm reds, and the mock turtle in green and cooler colors. Implied in the mock turtle’s comment bewailing that “once I was a real turtle” is the notion that things were better in the past, while currently he lives in the world of regretful thought. Conversely, with his eager “Come on!”, the gryphon lives in the world of action which savors the present.

“The Queen was in the parlor eating bread and honey”

Historically, in “children’s” stories, queens are involved in matters of food. Why food? Does it represent the only domain of authority for the matriarch? It would certainly seem so, as female power is traditionally asserted in our society in this one arena. Interestingly, the underlying psychology alluded to by Carroll’s characterization of the Queen, points to women’s “hysteria” not as an irrational outburst of exaggerated hormonally-driven insanity, but rather acknowledges the pent-up frustration of the female “leader” whose authority is relegated to the kitchen.

With savvy irony, Carroll articulates her rage in the words “Off with his head!”, when, in fact, as history has shown us, this will most likely be the outcome for her own head, as decapitation has been a common solution by the patriarchy to eliminate ‘the uncontrollable female’ (i.e. OJ Simpson). Parenthetically, please note that the Queen’s orders of execution are never carried out in the story. Ultimately, I assert that the Queen’s rage over seemingly minuscule tarts addresses the fact that, in truth, she is cognizant of her probable fate and that the fury we see is her aggravation at being powerless to change her destiny.

Other significant devices include:

1. Checkered table cloth references game board. Also, the four of clubs, plus the seven of clubs, plus the Jack of Hearts equals “21” in ‘Black Jack’.

2. “Here ye, Hear ye” serves as a play on words to reference Carroll’s frequent puns.

3. A looking glass is a mirror; hence, note mirroring of pink and green figures on right with those on left. Also, yellow duck mirrors blue walrus, pink flamingo mirrors gryphon (half-eagle, half-lion), and white bird mirrors lamb in lower right corner.

4. Alice as “innocent” destroyer (her growth spurt creates ‘tsunami-like’ tidal wave of catastrophic proportions); hence her petticoat suggests waves.

5. Queen is angry over more than tarts (“crystal ceiling” implied in cage-like tiara droplets).

6. King represents benevolently wise, yet oblivious, patriarchy.

7. Mad Hatter’s nervous exit embodies ‘flight from fright’ response. Also, White Rabbit (blowing trumpet) exemplifies fear-ridden employee.

8. Soldier represents upholder of institution (issues of glory and duty manifest).

9. Jack of Hearts represents the comprehensible foibles of humanity under a relentlessly rigid system of “justice”.

10. Stable structure in upper left references system of authority that is adamantly in place.

11. Chaos within system of order moves from upper right to bottom left (via recurrent orange triangular shapes) arriving ultimately to March Hare who receives the bounty in split-emotion of fear and elation (the treasured tarts represent a fluke fortuity akin to the lottery).

This image illustrates the ending of “Alice in Wonderland” when Alice awakes from her dream to find herself in the loving company of her dear sister who was tenderly brushing the fallen leaves from Alice’s sleeping face. I have depicted a few of the Wonderland characters in mid-fury at Alice’s audacious assertion that they’re “nothing but a pack of cards!” They begin to dissipate into falling leaves as Alice enters into consciousness.

One valuable aspect of this scene is that it offers a wonderful tribute to sisterhood, and the profoundly nurturing bond that it offers. Even more significant is Carroll’s characterization of the ramifications of refuting societal dictates. He suggests that to expose the impotence of social mores, (as Alice does in her emperor’s-new-clothes-like outburst), is to unleash the wrath and indignation of those who believe they have a stake in perpetuating the status quo. Encouragingly, he assures us that in actuality that seemingly gargantuan ire has the fortitude of a flimsy house of cards. He points to the misguided illusion that by insisting that the individual adopt socially-determined “appropriate” behaviors, that the society is better able to maintain order or control change. Of course, change is the uncontrollable nature of life. Nothing could be more natural than change. Logically, to vilify, impede, or resist change is in actuality an aberrant behavior. In the court scene, Alice was merely speaking her mind, objecting to the Queen’s demand “sentence first- verdict afterwards”. The Queen tries to silence Alice by threatening “Off with her head!”, however, Alice “had grown so large in the last few minutes that she wasn’t a bit afraid…”, (this celebrates the individual as being greater than the society). Alice is fundamentally modeling the behavior of a free-thinking individual. Additionally, Carroll alludes that those who obey society out of fear of ostracism, as do the White Rabbit and the jury members, are responsible for keeping that authority in place and assure its stronghold by way of conformity-induced complicity. By perceiving society as an entity greater than oneself that determines for everyone what is appropriate behavior, one absolves oneself of the responsibility to think, to concentrate, and to be consciously aware. Essentially, one is responsible in either case. Either one is responsible for one’s own thinking, or one is responsible for turning over that thinking to others. Since one cannot escape that responsibility, is it not wiser to keep the rein close-at-hand? Further, is it really so dangerous to nurture a population of individual free-thinkers who determine the best behavior for themselves? This is particularly true given the fact that regardless of compliant acquiescence or self-actualized maneuvering, a person is going to affect the society in either event and will unavoidably cause disturbances in the routine machinations of society. For example, Alice’s presence in Wonderland produced some potentially-detrimental, if not outright-destructive, effects. Upon entering their world, her tears cause a flood, she breaks the cucumber frame in the White Rabbit’s house, she nearly knocks the life out of Bill the Lizard when she kicked him out the chimney, she separated a child from its albeit-abusive mother when she set the pig-baby loose to fend for itself in the woods, and, of course, she completely upsets the court session simply by tripping over the jury box, sending the jurors crashing into the guests of the court. My point is that despite her consistent attempt at good manners, she quite thoroughly disrupts “business as usual”. One cannot avoid upsetting the apple-cart of society from time to time, nor can one avoid being the bad-guy on occasion. Given that complicity does not provide any insurance against social gaffes which may evoke the wrath of society, why not seek out one’s own ethos of personal integrity and value structures? Ultimately, Alice’s waking up to a real world, away from that make-believe dream-world of society, signals a new day, a fresh start, with her dear sister by her side.

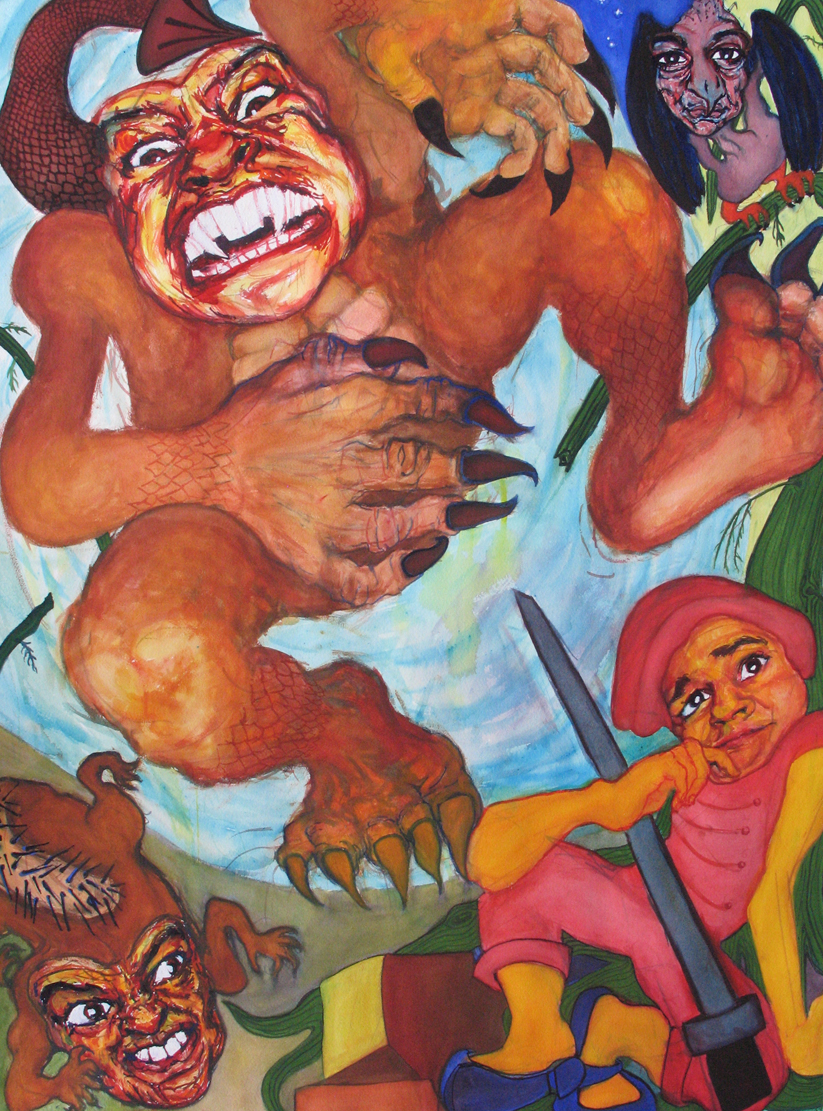

Though Sir John Tenniel (the original illustrator of the “Alice” books) depicted the Jabberwock as a dragon-like creature, I imagined him as a He-man gorilla jumping out of the lagoon. I envisioned the Bandersnatch as an insidious side-kick, and the Jubjub bird as an old vulture who believes the imminent outcome will be the death of the boy. I’ve handled the Tumtum tree as a bleak vegetation devoid of foliage with serpentine characteristics. Compositionally, the branches, in conjunction with the sword blade, form an “X” at the dangerous swiping hand of the Jabberwock which is about to kill the beamish boy. Though in the poem the boy is standing, I’ve placed him in a crouched position. I believe the unaware, pondering boy would have been unable to overcome the odds in this treacherous scenario, and that it is by sheer “dumb luck” that the Jabberwock inadvertently lands directly on the boy’s upturned sword, thereby killing himself by mistake.

The poem “Jabberwocky” from “Alice in Wonderland” by Lewis Carroll follows:

‘Twas brillig and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

“Beware the Jabberwock, my son!

The jaws that bite, the claws that catch!

Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun

The frumious Bandersnatch!”

He took his vorpal sword in hand:

Long time the manxome foe he sought-

So rested he by the Tumtum tree,

And stood awhile in thought.

And, as in uffish thought he stood,

The Jabberwock, with eyes aflame,

Came whiffling through the tugley wood,

And burbled as it came!

One, two! One, two! And through and through

The vorpal blade went snicker-snack!

He left it dead, and with its head

He went gallumphing back.

“And hast thou slain the Jabberwock?

Come to my arms, my beamish boy!

O frabjous day! Calooh! Callay!

He chortled in his joy.

‘Twas brillig and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

From the chapter entitled “Looking Glass Insects” from “Through the Looking Glass”, the train jump is Carroll’s way of facilitating the logic of Alice’s first move as a pawn on the chessboard, which is, of course, a two- square jump, (see “The Annotated Alice”). Using the train jumping off the rails as a metaphor for leaving the preordained path, I have created a piece that explores reactions to unexpected change, and therefore, this piece is predominantly a fear study.

One of the passengers is described as a gentleman in a paper suit. Noting that I’d only ever donned a paper garment in the hospital, and pondering why anyone would wear a hospital garment on a train, I decided to cast him as a mental patient gone AWOL. As he is not “normal”, he finds the unexpected jolt to be an exhilarating thrill. I see the beetle as the person who expects the worst to happen. He is quite sure he is doomed to be smashed. The horse, who is looking out the window, sees that the train is just jumping over a brook, and, because of his awareness and vantage point, reacts calmly to the event, serenely conscious of the transition. Alice, the guard, and the goat are frozen in the clutches of fear.

In studying these faces, I realized how fear and self-pity are closely linked. When one’s sense of self is threatened, “little ol’ me’ seeks mercy, and one’s consciousness shrinks, able to focus solely on one’s own cringing self. Conversely, the “insane” man’s consciousness is much broader, focusing its attention externally, riding the experience and savoring the change.

Compositional strategies which help to convey the jolting lurch of the train’s jump include:

1. Skewing the perspective of the train cabin in an attempt to disorient the viewer.

2. Using a warped, diamond-shaped, high-contrast tile pattern to destabilize the floor. Pattern simultaneously alludes to shadows of impending fallen luggage.

3. Trying to place the viewer in the scene as if s(he) was one of the unseen luggage cases threatening to fall on Alice and the goat, by way of the perspective and the focus of their eyes.

4.The lamp chain, guard’s binoculars, goat’s bell, window sashes, and half-door’s draping red curtain all help to suggest chaotic movement.

My "Ode to Joy". Harkens to Matisse's "Dancers" composition.

As I see it, the story of the Walrus and the Carpenter models a genocide scenario. The two have tricked the little oysters to come for a walk, luring them away from their home in the sea, in order to devour every last one of them. The fact that the Walrus is crying simultaneously suggests that despite an aggressor’s capacity for empathetic response, he will not act on that compassionate inclination, because to do so would be counter to the goal at hand. Hence, Carroll’s analogy points to the invariable necessitation of a third party to intercede with active humanitarianism in the case of genocide.

Relying heavily on the primary triad as a color strategy, this piece also includes the sulking moon which is unhappy as the sun is up at night, indicating Carroll’s interest in astronomy and eclipses.

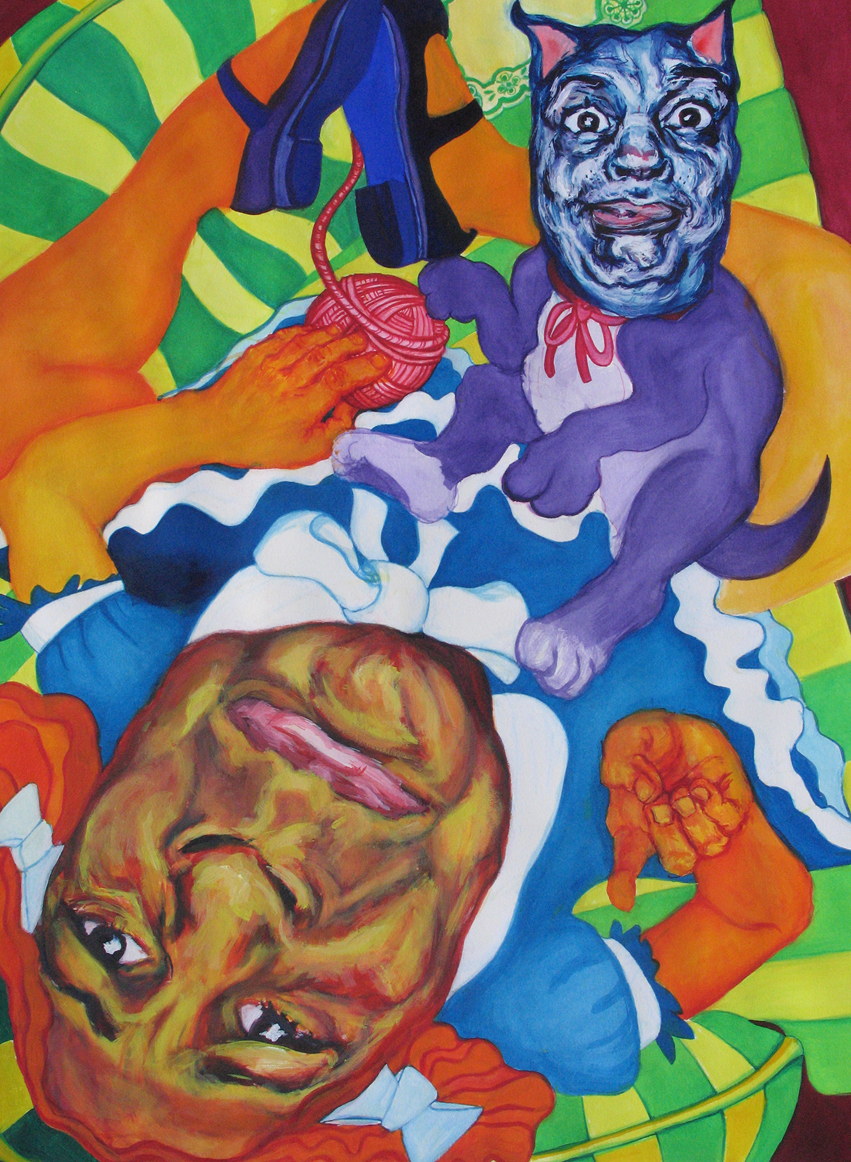

In this chapter from “Through the Looking Glass” in which the woods become a shop, and then the shop becomes a waterway with banks of rushes, we understand that Carroll is shifting landscapes in the style of dreamscapes. Alice is moving through a dream. Further, the White Queen has turned into a sheep, which, as “The Annotated Alice” astutely points out, is within her nature, as the queen can take on the form of any piece on the chessboard. I have taken the liberty of including in this image some of the Looking Glass insects that Carroll introduces earlier in the book, namely the elephant-bee and the rocking-horse-fly. As I am using this scene as a vehicle to articulate a piece addressing the cycles of life and contrasting attitudes about life, these insects represent the activities of sustaining life, as they feed on the riverbank flowers. I have placed daisies, as opposed to rushes’ in Alice’s hand, as daisies represent the babies of the flower world, (as we learn in the chapter entitled “The Garden of Live Flowers”). I felt that they better served my cycle-of-life interests, as their nascent innocence is sharply contrasted to their ensuing death at the hands of Alice who excitedly picks the little darlings. Considering Alice as taking lives with the capricious whim of a Greek god perhaps offers a useful image to one trying to understand the logic of death’s call, suggesting that it could be as arbitrary as a child collecting blossoms. Compositionally, I am endeavoring to “break the fourth wall”, suggesting that the viewer might be her next target. This is accomplished by: 1) using a primary triad in the lower right corner which causes the image to advance, 2) focusing her gaze at a point approximately three feet in front of the wall, 3) using a hand gesture that is in mid-grab, (which incidentally also contributes to Alice’s generally compromising position, referencing present-day speculations regarding Carroll’s possible sexual fixation on her), and 4) tilting the perspective of the front reed to heighten the illusion that it is leaning into real space. Another compositional strategy I employ is to counter the dramatic diagonal created by the boat by emphasizing the opposite diagonal created by the reeds arching to the other side. The crab merely references Carroll’s rowing-terminology joke, as the White Queen/Sheep cautions Alice not to “catch a crab”, or rather, not to dip the oars to deeply, (see “Annotated Alice”). The pseudo-hieroglyphics on the boat, the invented symbols on the cash register, and the avoidance of any specific currency on the paper money, are included to vaguely suggest cultures without limiting the image to any particular time frame or nationality.

Most significantly, the piece offers an emotional contrast, a mirroring, between Alice’s face in a state of wonder about life, and the White Queen/Sheep’s face in a state of disdainful disappointment about life. One has seen it all before, the other is seeing everything new for the very first time.

Alice, having just said “Hay and ham sandwiches” in a rhyming game with the king, is amazed to see that Haigha the Messenger pulls out none other than hay and ham sandwiches for His Highness’ lunchtime fare. Alice is now cognizant of the fact that she can and does affect the external world of the society. Her stream-of-consciousness thoughts, blurted out in words, and manifested into the physical world by way of the satchel that Haigha (who was the March Hare in the first book) carries, are realized through this seeming font for birthing ideas into the physical realm.

In my ongoing examination of Lewis Carroll’s Alice books, in which I cull the stories for emotionally-laden scenarios, this piece is predominately a self-pity image with its mirror response of empathy.

In this scene from “Through the Looking Glass” chapter entitled “The Lion and the Unicorn”, we see Haiga (previously the March Hare in the Wonderland book, now a castle messenger in the chess game), consoling Hatta (previously the Mad Hatter) who has just been released from prison. Here, the broken tea cup represents the seemingly- irreparable wound, as poor Hatta feels irrevocably scarred by the harsh humiliations and indecencies to which his delicate tea-loving spirit has been subjected. Haigha’s gentle, nurturing nature, (articulated with cooler reds and more gradual value transitions to suggest his milder emotional timbre), attempts to heal Hatta’s woeful soul by softly coaxing his recovery through the tenderness of love.

This depicts the final climactic scene in “Through the Looking Glass”, in which Carroll pokes fun at dinner party behavior in the drunken debauchery that ensues at the celebration of Alice’s crowning as queen. The guests, (animals, flowers, and birds), cheerily welcome Alice singing “…sprinkle the table with buttons and bran: Put cats in the coffee and mice in the tea”. However, once the red Queen encourages them to drink to Alice’s health, (which is accomplished by turning a wine glass over one’s head and licking the trickling treacle/ink or by knocking one’s glass onto the table and lapping it up as it runs off the edge), all hell breaks loose.

For the animals, I’ve depicted a skunk, bear, and squirrel in progressively drunker states. The three kangaroo-like creatures are greedily gobbling up the mutton gravy “…like pigs in a trough”. The frog livery man dressed in yellow and wearing boots represents the depressed drunk, and the soup ladle depicts the belligerent drunk. The tiger lily and rose in the bottom left corner are alarmed by the flying wine-bottle-with-dishes-and-forks ‘bird’ and the candles have burst into firecrackers. In an effort to stop the madness, Alice pulls the table cloth in a gesture akin to Jesus turning the vendors’ tables in the temple, sending the whole affair crashing to the floor. Carroll not only airs his disgust with orgiastic social displays of gluttony, inebriation, and greed in this culminating scene, he once again, (as in “Alice in Wonderland”), ends the story with the individual as being greater than the society, as Alice stands up and puts society in its place.

Compositionally, I have organized the information radially, with chaos branching out from the kangaroo-like creatures’ cluster. I have painted the dinner party’s table cloth white in order to draw a parallel with the white of the actual canvas. I aspire in this strategy to place the viewer in the role of Alice taking up the fabric in her hands and toppling society with one great tug.

The chapter entitled “The Wasp in a Wig” was omitted from “Through the Looking Glass” by Carroll in response to the illustrator Sir John Tenniel’s request, as Tenniel was running behind schedule and claimed he couldn’t identify any passages worth illustrating. The author of “The Annotated Alice” speculates that Tenniel’s resistance might well have had more to do with an aversion to the contents of that particular chapter. Tenniel had but one good eye due to a childhood fencing accident with his father, and possibly took offense to the wasp’s comment regarding the location of Alice’s eyes being so close together that she might as well have only one eye. In the story, the wasp is really an old man whose disposition is characteristic of a wasp and who looked like a wasp due to the bandanna tied around his head to hold up his wig, as the knots mimicked the shape and location of wasp eye-sockets. I’ve dressed him in a “yellow jacket” to contribute to his bee-like persona. His interest in the loss of less-expensive brown sugar, not white sugar, in the treacle accident at the lake, as reported in the newspaper article he’s found reading under a tree, places him in the lower class. The importance of this regrettably-edited scene, is that Alice’s gesture of kindness in stooping to help the shivering old man of a lower class to the sunny-side of the tree, signals not only her worthy passage into becoming a queen in the very next chapter, but also evinces her transition into maturity, as Alice was approaching her eighth birthday and was moving well out of Carroll’s favored age of six.

The most significant aspect of this scene with regard to Carroll’s social commentary, is that the wasp followed society’s suggestion to cut his hair, but it never grew back, and consequently was forced to wear the ridiculous wig for the rest of his life. This scenario reinforces Carroll’s consistent warning about following societal norms, asserting that to do so will invariably result in regret, and that one should instead listen to one’s own individual logic. Hence, the image that I have created is, at its core, a mirroring of mistrust and trustworthiness. The old man embodies the hurt of a lifetime of having trusted society and been wounded, whereas Alice represents a clean slate of pure benevolence. I’ve tried to convey this in the warm, healthy openness of her hand in contrast to the jaundiced, arthritic caution we see in his tentative, trembling hand. The notion of this perceptual polarity is visually evident in the mirroring of their hair shapes as well as the fact that the source portrait is the same person, inferring that one may manifest either side of this continuum of distrust and trust. Interestingly, Alice’s behavior in stooping to help the man from a lower class falls outside of the social norm and, by way of Carroll’s general formula, therefore falls within the realm of the trustworthy.